After spending the morning helping Dr. Tomasa attend to families at the walk-in office in Monte Carmelo, Jonas will jump on his motorcycle and head for Sanare for afternoon medical school classes.

After spending the morning helping Dr. Tomasa attend to families at the walk-in office in Monte Carmelo, Jonas will jump on his motorcycle and head for Sanare for afternoon medical school classes.Last Tuesday afternoon I joined the first-year medical students for classes. There are thirteen students from the Sanare area and seven new foreign arrivals from ELAM, La Escuela Latina America de Medicina (“the School of Latin American Medicine”) which has been training 20,000 foreign students in Cuba and now has opened up an associate branch in Venezuela this year. The idea is to give these new ELAM students the same training that Venezuelans are receiving in Integral Community Medicine.

Doctora Alina, the short, spunky Cuban who was teaching the class, looked a little grumpy when Doctor Umberto, the Cuban director of the local program, told her that I was going to sit in on her class. Perhaps she was wondering if her thirteen Sanare students would perform well on a short quiz on molecular genetics, the previous week’s focus of study; or perhaps she was skeptical about letting a curious, and possibly untrustworthy gringo observe the group. The seven new students – three from Surinam, two from Colombia, one from Brazil, and one from Peru – waited patiently outside while the others took the test because they had not been present for all of the classes during the previous two weeks.

After the quiz, Doctor Alina asked the students to orally explain concepts related to the quiz. Arelys, one of the students from Monte Carmelo, seemed to have no problem explaining the interactions among XX and XY and XYY chromosomes. Then the doctor turned to one of the foreign students, who have been catching up on the readings, and told him to set up a six-part chart related to “operadores, promotores, regulatores, y cistrones.” Frankly, I was a bit lost and so was this particular student, who had a large and sheepish grin on his face as he struggled to write things on the board. The grin didn’t appear to make the doctor happy, and while she refrained from scolding him personally she did suggest to the whole group that a serious commitment to study was necessary. One of the students from Surinam was asked to answer the same question and had no difficulty charting a diagram and explaining the required processes in detail.

Now it was time to change rooms. Up until this point we had all been squeezed into a crowded reception room which had a street entry door on one side, and in the opposite corner, a desk and a computer for Dr. Umberto, the director. He and Dr. Frank, the intensive-care doctor from Sanare’s Diagnostic Clinic were having a discussion about cardiac and arterial blockages. They were searching the internet for discussions of new procedures and then jotting down extensive notes related to the problem they had to solve.

The Sanare area had no intensive care doctor until Doctor Frank arrived from Cuba a few years ago. Now he works in the new Diagnostic Clinic that is equipped with sophisticated imaging equipment and other resources that previously could be found only in the big cities. He dropped by the offices of the Integral Community Medicine program to discuss new emergency treatments with the director. (Very observant readers will note that he is not the only Dr. Frank working in Sanare. The other, an ophthalmologist, appears in the first blog article about Cuban World MDs.)

When the third-year students came out of an adjoining classroom, our group of first-year students moved in there. This room was larger, quieter, and equipped with old-fashioned school desks and a computer and projector that was set up to show a DVD film to the students. Doctor Alina and the film split the lecture time -- about 65% for the Doctor and 35% for the film -- over the next two hours. The film was well-made, a succinct and informative discussion by a female narrator accompanying charts, drawings, and cartoons. This was different than what I had expected. I had developed the impression, in discussions with other Cuban doctors a year ago, that the new films used in classes were going to be videos of live lectures that had been presented by professors in Cuban universities.

This was not the case. The Cuban medical universities have prepared a whole set of video films designed specifically for the six-year program in Integral Community Medicine in Venezuela. We were watching “Morfofisilogia Humana (human morphophysiology): 1st trimester, 1st year.” Previously the Cubans have gained international recognition for the advances they have made in audiovisual education, especially with their new concepts of how to teach language and reading. While I am

ill-equipped to tell you whether this sophisticated or unsophisticated treatment of human morphology, I can say that I was captivated by the class.

Clearly the film was designed to be an interactive tool, and Doctor Alina made frequent use of the TV remote control to stop and start the action whenever she felt like it. She was very sharp and animated as she added detail, emphasized related material, or repeated the information in a fresh way to make sure the students were comprehending things. They felt free to ask questions at any time.

The general theme, which followed naturally on the previous week’s material, was human reproduction: how the cells of a baby are formed, and how a normal pregnancy is achieved. The “sumario” of the film announced associated themes: “Gametogenesis, Fecundacion, Desarollo de Cigoto, Alteraciones, Contracepcion.” After the film presented the different patterns of chromosomal joining and the exceptional cases, Doctora Alina pointed out some of the abnormal processes which were most likely to lead to birth defects. Later, when the film discussed the way in which the fertilized egg is implanted on the wall of the womb, she spent considerable time answering questions from students about unsuccessful pregnancies and the kinds of incorrect implantation that lead to spontaneous abortions, ectopic pregnancies, etc. “This is the kind of material you need to master,” she said, “because some day you’re going to have to explain these processes to some of your patients.”

After the doctor delved into “blastocistos, zona pelucida, trofoblasto” and other exotic (for me, at least) definitions, there was considerable discussion of the “feminine sexual cycle” and various ways to help women understand their individual variations from the average length of the period and the time of ovulation, including the use of a rectal thermometer. As it turned out, this discussion was related to the homework assignments. After Doctora Alina gave them the straightforward assignment of describing in detail the processes of “ovogenesis” and “spermatogenesis,” she went into different territory.

She gave them the hypothetical case of a long distance truck driver who is on the road most of the month and is married to a woman who travels throughout the country regularly to promote one of the new social missions in Venezuela. They’ve been married for three years and she can’t get pregnant. “What would you, as their doctor,” she asked, “advise them to discuss? And what measures could they take to better their chances of having a child?”

One of the students anxiously waved his hand and said, “I think I read an article about long-distance truckers and the possibility that because of all the time they spend sitting immobile in the cab this is cutting down on their sperm production.”

The doctor rolled her eyes toward the ceiling, and then shook her head emphatically, “No, no, no, that’s a bit of hypothetical speculation and it’s not the avenue of inquiry you should be pursuing, since there is a more straightforward approach that should probably solve this couple’s problem.”

Her last homework question was also intended to make them, as young medical people, practice sharing their knowledge and developing sympathy for the people they will treat: “You are in the walk-in clinic in some little village or in a Barrio Adentro office in a poor barrio, and a young woman comes in and says, ‘I’m think I’m pregnant. But I don’t know how I got pregnant.’ What do you need to ask her? What do you need to explain to her?”

The program of Integral Community Medicine is designed to mix intensive practical experience and intensive classroom study in each year of the six-year course. In another three years or so, when those students who are now in their third year graduate, we will see if this new course of study has produced a new kind of doctor. For now, from my visit to the first class in the first trimester of study, I can say that special attention is being devoted to the concepts of “integral” and “community.” In this process, both the curriculum and the professors are coordinated in a systematic effort to develop the humanitarian and humanistic potential of this very special vocation.

Dr. Alina provides the broad humanistic perspective without giving an inch on rigorous expectations of her students. They say she's the toughest taskmaster of the Cuban doctors in Sanare, all of whom demand the strictest attention and professionalism from the students whether they are in the classroom or assisting in the medical offices. After the class, however, she was all smiles and invited me to come visit her at her morning job, the Barrio Adentro clinic in one of the poorest neighborhoods of Sanare.

Who can aspire to this vocation?

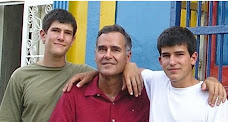

Anyone who passes the preliminary exam and the six-month premedical training course is admitted. One of the first-year students in Sanare is José, a fairly old guy -- according to his fellow classmates, he's either seventy-one years old right now, or will be seventy one when he graduates in six years. He told me that forty-five years ago he was a supporter of the revolutionary guerrillas and was carrying supplies to them in their hideouts in the mountains in this region. “I was born a socialist,” he said as we walked away from the classroom building, “so this is a good way for me to finish out my life.”

The younger students say they are proud of him and glad he got a chance to qualify for the training in spite of his age. He says, with a big grin, that he hopes to practice medicine til he’s one hundred.

Anyone who passes the preliminary exam and the six-month premedical training course is admitted. One of the first-year students in Sanare is José, a fairly old guy -- according to his fellow classmates, he's either seventy-one years old right now, or will be seventy one when he graduates in six years. He told me that forty-five years ago he was a supporter of the revolutionary guerrillas and was carrying supplies to them in their hideouts in the mountains in this region. “I was born a socialist,” he said as we walked away from the classroom building, “so this is a good way for me to finish out my life.”

The younger students say they are proud of him and glad he got a chance to qualify for the training in spite of his age. He says, with a big grin, that he hopes to practice medicine til he’s one hundred.

José wanted to know what was new with the primary elections in the United States, and I replied that Obama appeared to be edging out Hillary. “That’s good,” José said, “but do you think he wants to end that insane war in Iraq?”

“I wish I could say yes, but I really don’t know,” I said.

“Well, if he gets elected and says he’s going to pull the troops out, he had better watch his back. I am afraid they’ll try to assassinate him within five months.”

5 comments:

This is really interesting, You are a very skilled

blogger. I've joined your rss feed and look forward to seeking more of your great post. Also, I've shared your

web site in my social networks!

my site: free way to make money online

What's up to every body, it's my first pay a visit of this website;

this blog contains amazing and actually fine information for visitors.

my page :: binary options course

Hi my loved one! I wish to say that this post is awesome, great written and

include almost all vital infos. I'd like to see extra posts like this .

Feel free to visit my web blog :: how does a free website make money

My website > how to make a money making website for free

Having read this I believed it was really enlightening.

I appreciate you finding the time and effort

to put this information together. I once again find myself spending a lot

of time both reading and posting comments. But so what, it was still worthwhile!

my website - Binäre Optionen

Hello, I read your new stuff daily. Your humoristic style is awesome, keep doing what you're doing!

Check out my web-site Binäre Optionen

Post a Comment