At “La Feria de Libros,” or Book Fair, there were giant white tents with a million books and thousands of people inside. The tents were scattered over several acres in the Parque del Este in downtown Caracas. Publishers from all over Venezuela and Latin America showed their wares, and the public was invited to attend at least six venues, each in a separate tent, for cultural events and lectures.

For once leftists from the U.S.A. put aside their differences (mostly) and were willing to gather under ‘a big tent,’ the Salon Joe Marti.

For once leftists from the U.S.A. put aside their differences (mostly) and were willing to gather under ‘a big tent,’ the Salon Joe Marti.

Ari and I hopped on a few buses and ten hours later we were in Caracas, only a day and a half late. At the last moment, I had been invited to take part in presentations and panel discussions at the Fair. The organizers not only put us in a nice hotel, but they were willing to feed my son, who can decimate any buffet in the world.

There were other writers and activists from the United States, including some who have lived in Venezuela for many years, like Charlie Hardy and Eva Golinger, and others who were making brief cultural visits, like Luis Rodriguez and Tufara LaShelle Waller. We were asked to speak at different times over a five-day period on the topic: “Will there be a revolution in the United States?”

I was tempted to say, “When Hell freezes over,” since it’s difficult to imagine that the U.S., with or without a Bush at the helm, is going to stop acting on behalf of transnational capital and join the wave of change sweeping over the Americas. But on the second day of presentations by my fellow North Americans, I was struck by the optimism of three Latinos, Antonio Gonzalez, Diogenes Abreu, and Luis Rodriguez, who tended to take a long-term perspective. They see the revolutionary potential slowly growing, born of the harsh working-class experience of most Latinos and Afro-Americans and an increasing number of poor whites. For Latinos in particular, there is also the influence of new ideas seeping into the United States via the progressive Hispanic political movements in Central America, South America, and the Caribbean.

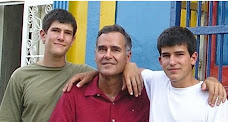

We got to hang out with Luis Rodriguez (on the left), Mexican-American activist and author of La Vida Loca. Ari loved his stories about gang life in LA.

We got to hang out with Luis Rodriguez (on the left), Mexican-American activist and author of La Vida Loca. Ari loved his stories about gang life in LA.

Antonio Gonzales emphasized the fact that small changes, even ones that seem like slow reforms, can have a cumulative revolutionary effect for working class people. He thinks that the changing racial configuration of the United States, most dramatically in his home state of California, is producing a more progressive political culture. Graphs in his slide show referred to Census data that predict that 50% or more of the U.S. population will be non-white by the year 2050.

As Diogenes Abreu, a Dominican activist from NYC, talked, he also displayed one of our favorite T-shirts. We have the same Homeland Security t-shirt at home in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, where it’s protecting a piece of beautiful land that once belonged to an Apache named Dick Kaseeta, who at 4 years old was the youngest “student” (prisoner of war) ever to attend the Carlisle Indian School.

On the final day of these sessions, I found myself leading off the presentations in a more optimistic mood. “History teaches us that we should always be ready for dramatic change. Look at the 1920s,” I said, “a backward decade by anyone’s standards, when the rich multiplied their fortunes at the expense of everyone else and controlled the political arena; when membership in the KuKluxKlan surged not just in the South, but in the North, in tandem with increased racist attacks against African Americans and poor European immigrants; when harsh repressive tactics dramatically reduced union membership and strike activity; when rampant gambling on Wall Street drove the stock market to absurd heights and endangered the economy.

“The 1920s were as reactionary as our present era, which began with Reagan and Bush I in the 1980s. Under Bush II, we have reached degrees of economic inequality and crazy financial speculation that are actually as bad as the 1920s. Perhaps times are ripe for a sudden lurch to the left.

“Remember what happened after the 1920s? The next decade, the 1930s, was one of the most progressive in our history. It was not exactly a revolutionary decade, but was characterized by extraordinary labor organizing and major political and economic reforms: there were the sit-down strikes in major industries and changes in labor law that let union membership boom; there were major relief and cultural programs sponsored by the federal government to counteract the effects of the Great Depression; there was the passage of the Social Security laws; and there was a huge increase in the rate of taxation on the very rich. These changes helped initiate a dramatic shift toward economic equality in the U.S. which, over the next four decades, allowed a very large section of the working class (particularly white people, since racism was not wiped out so easily) to enjoy a more or less ‘middle class’ existence.”

I’m afraid that when I tried to explain our current economic mess and the new kinds of destructive financial speculation, I stepped beyond the limits of coherent translation. For who is going to be able to understand the meaning of “hedge funds” and “negative derivatives” in Spanish when these terms are meant to confuse people in English. Luckily, my three fellow speakers came to my rescue with presentations that were more lucid than mine.

Dada Maheshvarananda, a member of the Ananda Marga association, was dressed in orange robes as he presented a sophisticated slide show that described the philosophy and activities of his organization. Dada is the author of After Capitalism: Prout’s Vision for a New World, which he and his associates are trying to implement by working in the Afro-Venezuelan region of Barlovento. With government encouragement they have held numerous workshops and training sessions with groups of farmers and cacao growers who already work in cooperatives or are interested in forming them.

Finally, to end the session on a strong note of artistic performance, we heard from Amina and Amiri Baraka, the revolutionary activists and poets from Newark, New Jersey. Both emphasized that revolution is possible in the United States, and is particularly necessary for Afro-Americans so that they can complete the process begun by Black Revolutionaries in the 1950s and 60s. Amiri reminded the audience that the United States had the first successful revolution, so it was ridiculous to say that we are incapable of launching another one. Then he gave a powerful reading of “Somebody Blew Up America,” the poem that said so much about centuries of home-grown terrorism that it cost him his job as the Poet Laureate of New Jersey.

Amina Baraka read her poem while being accompanied by Pablo, a Venezuelan jazz saxophonist. The poem, Black and Brown Americans, begins like this:

We are

Chained to a trail of tears

We are

Tied to the Rope Around Nat Turner’s Neck

Our tongues are Twisted

Unable to Speak Our Language

Our Culture Ravaged

We stepped in Time with Dance

To Free Our Spirit

We Hear Birds

Of All feathers Fly –

The wind Sings …

For once leftists from the U.S.A. put aside their differences (mostly) and were willing to gather under ‘a big tent,’ the Salon Joe Marti.

For once leftists from the U.S.A. put aside their differences (mostly) and were willing to gather under ‘a big tent,’ the Salon Joe Marti.Ari and I hopped on a few buses and ten hours later we were in Caracas, only a day and a half late. At the last moment, I had been invited to take part in presentations and panel discussions at the Fair. The organizers not only put us in a nice hotel, but they were willing to feed my son, who can decimate any buffet in the world.

There were other writers and activists from the United States, including some who have lived in Venezuela for many years, like Charlie Hardy and Eva Golinger, and others who were making brief cultural visits, like Luis Rodriguez and Tufara LaShelle Waller. We were asked to speak at different times over a five-day period on the topic: “Will there be a revolution in the United States?”

I was tempted to say, “When Hell freezes over,” since it’s difficult to imagine that the U.S., with or without a Bush at the helm, is going to stop acting on behalf of transnational capital and join the wave of change sweeping over the Americas. But on the second day of presentations by my fellow North Americans, I was struck by the optimism of three Latinos, Antonio Gonzalez, Diogenes Abreu, and Luis Rodriguez, who tended to take a long-term perspective. They see the revolutionary potential slowly growing, born of the harsh working-class experience of most Latinos and Afro-Americans and an increasing number of poor whites. For Latinos in particular, there is also the influence of new ideas seeping into the United States via the progressive Hispanic political movements in Central America, South America, and the Caribbean.

We got to hang out with Luis Rodriguez (on the left), Mexican-American activist and author of La Vida Loca. Ari loved his stories about gang life in LA.

We got to hang out with Luis Rodriguez (on the left), Mexican-American activist and author of La Vida Loca. Ari loved his stories about gang life in LA.Antonio Gonzales emphasized the fact that small changes, even ones that seem like slow reforms, can have a cumulative revolutionary effect for working class people. He thinks that the changing racial configuration of the United States, most dramatically in his home state of California, is producing a more progressive political culture. Graphs in his slide show referred to Census data that predict that 50% or more of the U.S. population will be non-white by the year 2050.

As Diogenes Abreu, a Dominican activist from NYC, talked, he also displayed one of our favorite T-shirts. We have the same Homeland Security t-shirt at home in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, where it’s protecting a piece of beautiful land that once belonged to an Apache named Dick Kaseeta, who at 4 years old was the youngest “student” (prisoner of war) ever to attend the Carlisle Indian School.

On the final day of these sessions, I found myself leading off the presentations in a more optimistic mood. “History teaches us that we should always be ready for dramatic change. Look at the 1920s,” I said, “a backward decade by anyone’s standards, when the rich multiplied their fortunes at the expense of everyone else and controlled the political arena; when membership in the KuKluxKlan surged not just in the South, but in the North, in tandem with increased racist attacks against African Americans and poor European immigrants; when harsh repressive tactics dramatically reduced union membership and strike activity; when rampant gambling on Wall Street drove the stock market to absurd heights and endangered the economy.

“The 1920s were as reactionary as our present era, which began with Reagan and Bush I in the 1980s. Under Bush II, we have reached degrees of economic inequality and crazy financial speculation that are actually as bad as the 1920s. Perhaps times are ripe for a sudden lurch to the left.

“Remember what happened after the 1920s? The next decade, the 1930s, was one of the most progressive in our history. It was not exactly a revolutionary decade, but was characterized by extraordinary labor organizing and major political and economic reforms: there were the sit-down strikes in major industries and changes in labor law that let union membership boom; there were major relief and cultural programs sponsored by the federal government to counteract the effects of the Great Depression; there was the passage of the Social Security laws; and there was a huge increase in the rate of taxation on the very rich. These changes helped initiate a dramatic shift toward economic equality in the U.S. which, over the next four decades, allowed a very large section of the working class (particularly white people, since racism was not wiped out so easily) to enjoy a more or less ‘middle class’ existence.”

I’m afraid that when I tried to explain our current economic mess and the new kinds of destructive financial speculation, I stepped beyond the limits of coherent translation. For who is going to be able to understand the meaning of “hedge funds” and “negative derivatives” in Spanish when these terms are meant to confuse people in English. Luckily, my three fellow speakers came to my rescue with presentations that were more lucid than mine.

Dada Maheshvarananda, a member of the Ananda Marga association, was dressed in orange robes as he presented a sophisticated slide show that described the philosophy and activities of his organization. Dada is the author of After Capitalism: Prout’s Vision for a New World, which he and his associates are trying to implement by working in the Afro-Venezuelan region of Barlovento. With government encouragement they have held numerous workshops and training sessions with groups of farmers and cacao growers who already work in cooperatives or are interested in forming them.

Finally, to end the session on a strong note of artistic performance, we heard from Amina and Amiri Baraka, the revolutionary activists and poets from Newark, New Jersey. Both emphasized that revolution is possible in the United States, and is particularly necessary for Afro-Americans so that they can complete the process begun by Black Revolutionaries in the 1950s and 60s. Amiri reminded the audience that the United States had the first successful revolution, so it was ridiculous to say that we are incapable of launching another one. Then he gave a powerful reading of “Somebody Blew Up America,” the poem that said so much about centuries of home-grown terrorism that it cost him his job as the Poet Laureate of New Jersey.

Amina Baraka read her poem while being accompanied by Pablo, a Venezuelan jazz saxophonist. The poem, Black and Brown Americans, begins like this:

We are

Chained to a trail of tears

We are

Tied to the Rope Around Nat Turner’s Neck

Our tongues are Twisted

Unable to Speak Our Language

Our Culture Ravaged

We stepped in Time with Dance

To Free Our Spirit

We Hear Birds

Of All feathers Fly –

The wind Sings …

No comments:

Post a Comment