They are called Los Morochos – “the twins.” Juan José Escalona and Juan Ramón Escalona are identical, immediately recognizable with their shaggy hair and beards, and known by just about everybody in the Sanare area. And they, in turn, know just about everything that is to be known about Sanare and Monte Carmelo, from the days of prehistory to the present day.

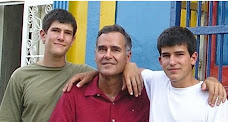

They are called Los Morochos – “the twins.” Juan José Escalona and Juan Ramón Escalona are identical, immediately recognizable with their shaggy hair and beards, and known by just about everybody in the Sanare area. And they, in turn, know just about everything that is to be known about Sanare and Monte Carmelo, from the days of prehistory to the present day.El Negro Morocho (“the black twin”), on the left above, is also known as “the anthropologist” because he has been studying the local population, its origins and its habits, all his life. He never had the opportunity to attend a university as a youth, but he has written ethnographic studies and books on the history and oral traditions of the area. Scholars from other parts of Venezuela visit Sanare to consult with him. Currently he is also employed in the restoration of ancient relics, particularly pottery, at the nearby archeological museum in Quibor.

Then there’s El Catire Morocho (“the light-colored twin” who really isn’t any whiter than his brother – Venezuelans simply like to give each other goofy nicknames like that.) He likes to draw, paint, and write long, narrative poems about political and social events of local and national interest. He is currently employed by the local school district to as a social worker/protector of abused and neglected children. He also encourages neighborhood kids to paint and draw, which means his house is piled high with local art, plus almost any other collectible artifact you can imagine. For instance, “los palos,” or sticks – there’s a big basket full of these next to their couch.

These “palos” aren’t just any sticks, but the traditional walking and fighting sticks once carried by the indigenous people in the surrounding countryside. They aren’t big, a little less than three feet long and about an inch in diameter, but sturdy enough to support one’s weight on the steep mountainsides or to dispatch a sharp blow to a wild pig or dog, a snake in the path, or a disagreeable human intruder. Some are completely plain and stripped of their bark, others are carved and decorated with feathers or paint and serve a variety of ceremonial purposes, especially in the dances that are native to the area.

The view of Monte Carmelo from the Morochos´ farmhouse

The Morochos share some local history

On Sunday, I climbed up the steep and rutted road that twists up the mountainside and leads to the family farm of the Morochos. The Escalona family, which includes their five brothers and sisters (two others have passed away), uses the house on weekends and lends it out for free to various groups and individuals who need to retreat or meet in a tranquil spot. They also let their neighbors graze their cows and pick berries on their ten acres of land.

Both Morochos were relaxing after taking a leading role in a nine-hour meeting on Sustainable Argiculture and the Revolution that took place in Monte Carmelo the day before. But, as always, they were happy to spend a few hours talking, so they filled me in on some personal and local history.

The Morochos now reside in a house in Sanare with their sister and her kids, but the farmhouse was their home as children. After they completed elementary school (the only school in Monte Carmelo in those days), the boys began a rigorous routine: they milked the cows and did other farm chores in the morning, then walked an hour and a half to Sanare to attend the liceo (which is equivalent to middle school and high school combined.) It was a four-mile hike on the winding road that descends a thousand feet to the valley below, then climbs back up about four hundred feet to Sanare. When they made the arduous climb back home, it was dark.

They didn’t mind the trip because life became exciting in the mid-1970s for fourteen and fifteen year-olds. The mountainous regions of Lara and other neighboring states were home to clandestine groups of armed revolutionaries in those days. These rebels were fairly inactive as far as fighting was concerned (the government had already crushed more serious guerrilla rebellions in the 1960s), but they were helping to stir up local protests on behalf of the campesinos who helped shelter them, and were working with other political activists who were not so interested in armed rebellion.

This latter group included the Morochos and other politically active high school students who developed contacts with the different clandestine groups: one group was loyal to a revolutionary named Douglas Bravo, another was associated with the Socialist League, and a third was called El Comite Lucha Popular (the Committee for the Battle of the People). The youths distributed newspapers printed by all three revolutionary factions and their followers, and they joined popular protests over the conditions that local campesinos had to endure: deteriorating schools, lack of health care, and poor quality drinking water.

Within a short time, the Morochos and their fellow students formed their own group, “2 Febrero” (named after the date of a student uprising during Bolivar’s War of Independence), that met regularly to study local problems and work on solutions. Their biggest contribution was their own political magazine, called “Tizon,” which they published regularly for five years.

At the same time that high school kids were learning how to take part in effective protests in Sanare, a few of them were also influenced by a new development in Monte Carmelo.

Three priests, two of them Italians, had come to Venezuela in 1975-76 after being driven out of Argentina by the wave of government terror and repression that swept through the countries of the Southern Cone in those years. They were members of the religious congregation called the Little Brothers of Jesus (a French order of worker/priests committed to living among the poor), and they settled in the hamlets of Monte Carmelo and nearby Bojo.

One of these priests, Arturo Paoli, was an influential thinker and writer in the ranks of those who created a “theology of liberation” in Latin America. Some of his books, such as “El rostro de tu hermano,” were written during his years in Monte Carmelo. As in thousands of other places throughout the Americas, Catholics were forming “base communities” that were determined to change the Church – they wanted to take a hierarchical institution with centuries-old loyalty to the elite, and re-form it into a “people’s church” that would meet the spiritual and material needs of the common people and the poor.

Various people gathered around Arturo Paoli in Monte Carmelo, including campesinos from the fields and students like the Morochos, and they discussed all kinds of things that could effect their lives: an understanding of the Bible and Jesus’ message to the poor, the history of Latin America and Europe, the social inequalities that affected land ownership and food production, and the usefulness of Marxist ideas about the political economy.

Out of this fertile mix of politics and religion new kinds of local institutions emerged. For instance, there was a highly popular theatre group that wrote and performed plays that outlined the history of rebellions and protests in the area. There were also two initiatives that survive to this day: the creation of farming communities that produce high quality, mostly organic food, and the idea of a “campesino university” that would serve rural people who never had the opportunity to attend high school or college. Both of these ideas are embodied today in the activities of La Cooperativa Mixta La Alianza, which is currently teaching other cooperatives in Venezuela how to organize and how to farm.

Dintas

Over the years, the Morochos have found time to keep writing about local history and legends. One outstanding work that they produced jointly is called Dintas, the ancient Indian name for the Sanare area (the Andres Eloy Blanco municipality); it was published as a complementary school text with the approval of the Education Ministry of the State of Lara in 1997. This illustrated, 110-page book is designed to introduce elementary school students -- 4th, 5th and 6th graders -- to the history and geography of the area.

Dintas traces the course of historical change over thousands of years and gives a vivid depiction of the natural environment, and it also urges students to make some historical and social judgments: “Are we living as happily as our ancestors, the Coyones Indians, did in ancient times? What good things and bad things have happened over the centuries? How are we going to make this little piece of Venezuela turn back into the paradise that we would like?”

(Another blog entry on Bolivarian Education and the Cooperative will appear soon.)

No comments:

Post a Comment